Proving the value of in-orbit microgravity manufacturing of purer, higher-performance semiconductor materials has been going on for over 50 years by a handful of countries conducting experiments and demonstrations, many on the International Space Station (ISS). Private industry is taking that work to another level, with development milestones stacking up.

SkyLab, Mir and the Space Shuttle did in-orbit semiconductor manufacturing beginning in 1973. Five experiments were performed during the Skylab 3 mission alone from July through September, 1973; in 1992, the first U.S. microgravity laboratory was featured onboard STS-50 after initial setup tests in the 1970s.

The U.S., Germany, Japan, and China have all logged experiments in developing semiconductor materials on labs in space with varying degrees of success, with India slated to join their ranks in 2035 with its Bharatiya Antriksh Station.

The space manufacturing legacy of ISS lives on, but its days are numbered. NASA is working out details about how to de-orbit ISS by 2030 using a special spacecraft to help.

The coming loss of ISS as a manufacturing platform has led to the development of commercial manufacturing space stations to be launched soon, such as Orbital Reef, by Sierra Space and Blue Origin; Axiom Station, by Axiom Space and Thales Alenia Space; and Starlab, a joint venture of Voyager Space and Airbus with a target launch date of 2029.

More commercial space companies are forming partnerships based on that crystals-in-space manufacturing legacy from the ISS—many with NASA darling United Semiconductors.

In 2022, NASA awarded funding to United Semiconductors to produce semimetal-semiconductor composite bulk crystals and validate the scaling and efficacy of producing larger semimetal-semiconductor composite crystals under microgravity conditions, launching the first of its kind semiconductor crystal manufacturing experimental payload to the ISS on the SpaceX-31 commercial resupply mission in November, 2024.

United Semiconductors is working now in a partnership with Aegis Aerospace, a provider of turn-key space services, spaceflight product development and engineering services for the civil and commercial space and defense industries to expedite the commercialization of semiconductor manufacturing using the company’s advanced materials manufacturing platform.

United Semiconductors is producing semimetal-semiconductor composite bulk crystals used in electromagnetic sensors with Redwire, a space infrastructure developer, and Axiom Space, a spaceflights service provider now building a commercial space station.

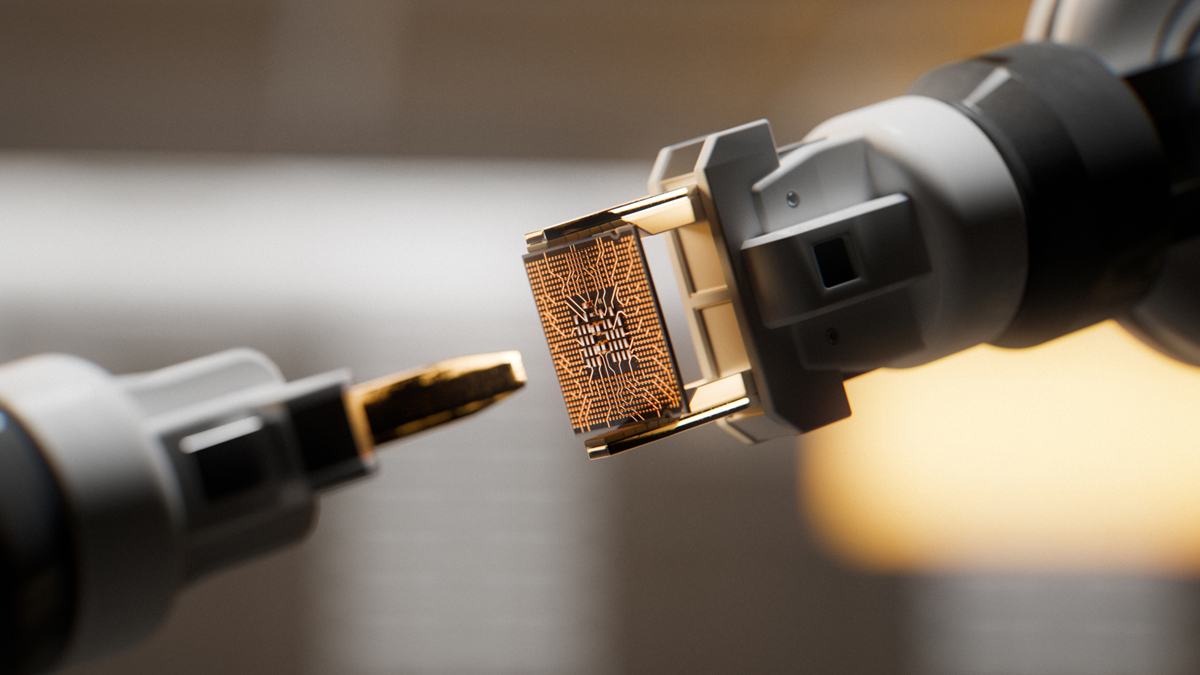

A Semiconductor Milestone

Space Forge is also working in a partnership with United Semiconductors to build microgravity-as-a-service for in-space manufacturing. It generated plasma in a demonstration aboard its ForgeStar-1 cubesat in LEO orbit in December—the UK’s first in-orbit advanced manufacturing satellite—six months after it was launched aboard the SpaceX Transporter-14.

The plasma demonstration, created and controlled autonomously, featured the use of an 1,832 degree Fahrenheit furnace. It confirmed that the extreme conditions needed for gas-phase crystal growth up to 4,000 times purer than terrestrially manufacturing crystals was possible, and greatly improved on what the ISS offered.

ForgeStar-1 will focus on growing wide- and ultra-wide bandgap materials such as gallium nitride (used in 5G/6G, radar and satellite communications), silicon carbide (used in EVs, fast chargers and power grids), aluminum nitride (used in RF devices and lasers), which are difficult to produce terrestrially because of defect formation, impurity incorporation and thermal instability during growth. Wide bandgap materials operate at higher temperatures, voltages and frequencies, making them good to use as smaller and more efficient components for lower cost, high-power applications.

This time, the spacecraft will be de-orbited and burn up in space. Space Forge plans another mission soon to incorporate what was learned from the plasma demonstration.

Going forward to their next missions, they hope to return space-grown “seeds” of crystal materials on the same satellite on which they were grown, using a deployable non-ablative heat shield for a soft landing to be recovered by a Space Forge team and refurbished ready for the next flight, then send the seeds to a lab for additional growth into larger crystals.

“This mission was not a one-off demonstration,” Atul Kumar, head of semiconductors in the U.S. for Space Forge said. “We have been doing over 40 [experiments] so far, and with each experiment, we get a lot of critical data for the hardware validation as well. It’s been very consistent, repeatable and reliable from the hardware perspective, and that’s an important milestone as well.”

The payload on this mission is a smaller version of the actual payload that Space Forge envisions for the next mission. “It’s a smaller prototype proof of concept demonstration,” Kumar said. “But a lot of key features are similar to what we would have on the next mission as well, like the plasma and the hardware.”

The company’s long-term vision is to combine this orbital crystal growth with terrestrial processing, creating a hybrid manufacturing model that complements existing supply chains rather than replacing them.

The Suborbital Contribution

Most in-space manufacturing has been done in LEO. But even suborbital flights are getting into the business of semiconductor manufacturing. For example, Purdue University will send its own five-person crew aboard a Virgin Galactic spacecraft in 2027 to demonstrate in-space chip manufacturing. The suborbital flight will give researchers about 3 minutes of microgravity time. “We are not just testing a process,” said Ajay Malshe, director of Purdue’s Center for In-Space Manufacturing in a Purdue press release, “we are architecting the foundation of the space economy.” Virgin has also partnered with Redwire for ongoing microgravity payload experiments.

It’s All About Scaling Up Now

Manufacturing semiconductor crystals in space can become an integral part of the semiconductor fabrication capacity projected to increase by 203%, according to report by the Semiconductor Industry Association. Growing crystals is the focus right now—assembling an entire transistor-level chip in space (lithography, etching, layering) may come later.

But first, space manufacturers need help in making what they want to do now economically feasible—cheaper launches, a better infrastructure, trusted logistics—in an effort to create parity with the $5 billion cost of single terrestrial crystal production facility.

According to NASA researchers in a 2018 report, the development of commercial launch systems has substantially reduced the cost of space launch. NASA’s space shuttle had a cost of about $1.5 billion to launch 27,500 kg to Low Earth Orbit (LEO), or $54,500/kg. Today, a launch of a small satellite on a SpaceX rideshare can be done for as little as $350,000 for 50 kg., or $7,000 per kilogram.

Now there is a growing trend among commercial space business developers to get more involved in organizing the necessary critical space ecosystem of launch, manufacture, and return to earth to scale up in-space semiconductor manufacturing.

“Right now, the issue you have in space is that you don’t have that ecosystem available,” said Farouk Abdulhamid, working on his PhD in the Department of Management, Economics, and Industrial Engineering, Politecnico di Milano technical university in Milan, Italy. “You don’t have that supply chain. Everything is just in the form of experimentation. Can we actually draw conclusions about the ability to manufacture in space based on limited controlled experiments? So I can manufacture a chip in a spaceport. Does it outweigh the cost that takes me to get to space, the launch cost and everything, that now makes it better than what I can manufacture basically one kilometer away from me? These are the challenges that remain, at least from my perspective. When I look at it, not from a technical aspect, but from a social and economical aspect, I ask myself is this good enough to be profitable?”

A comprehensive definition that encapsulates the full scope of factory-in-space as a unified ecosystem remains inadequately articulated, Abdulhamid wrote in a November, 2025 white paper that sought to provide an operational definition of the factory-in-space ecosystem by analyzing its components, features, and functions.

A business model that these early in-space manufacturing companies are following is building their own satellites, doing novel in-space manufacturing, then returning the manufactured materials, according to Andrew Parlock, founder and CEO of Space Phoenix Systems (also the former managing director of Space Forge) working on space logistics infrastructure.

“We don’t do that terrestrially,” Parlock said. “Terrestrially, semiconductor manufacturers make semiconductors. Then third-party logistics providers ship the stuff. That’s an efficient market where each company has a niche and is managing their niche. We’re forced into this hyper vertical, inefficient market. I want a company like Space Forge to be the best semiconductor manufacturer they can be. If they’re bifurcating their resources, if they’re bifurcating their investment dollars, they’re not going to do it. They don’t have to worry about this logistics infrastructure. That’s the boring part.

“Semiconductor manufacturing for the US is a national security imperative. So if we can make semiconductors 10x more efficient in space, my goodness, let’s get to it, and let’s build it. Let’s build the companies at the bleeding edge, and let’s build the support structure to make it work for them. You’re going to have to have all-hands-on-deck. That means all of America’s allies. We have to support it all,” he said. “The launch problem is solved. Now the next problem is infrastructure. The next problem after that is more commercial companies. Next problem, doing it at scale.”

Sorting Out Policy Complications

Manufacturing semiconductors materials in space could become competitive to terrestrial manufacturing within ten years or so, according to Sterling Thomas, chief scientist in the office of science, technology, assessment, and analytics for the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Thomas worked on a GAO report about future technologies that affect society. “The role that we play is helping Congress understand the semiconductor manufacturing in space technology, but also understand what they can do to adjust whatever levers they want.”

They talk about what manufactured in space means. “If something is produced in space, where was it manufactured? Was it manufactured in the U.S. by a U.S. company? Or was it manufactured in Russia, because maybe it was launched in Russia,” he said. “The next thing is, how do you import it? It comes back down, it lands in the ocean. Does it go through customs? The trickier one that was really fascinating is that, once you produce something and you try to bring it down, how do you license re-entry? It seems like it’s technologically complicated, but it’s also policy-wise complicated.”

Explore More:

4 Takeaways: Terran Orbital on the Industrialization of Space

What Quantum Machine Learning Can Do for the Space Sector

Constructing the Next Space Age