Imagine booking a first-class ticket across the country only to land and have to walk from the airport to your destination. This is essentially the situation satellites face today. Launch vehicles and rideshares ferry payloads from Earth to orbit with unprecedented efficiency, but the final leg is typically left to the satellite’s own propulsion system.

It’s the ultimate last-mile problem: getting satellites from a transfer orbit to their final destination. Today, a growing number of space logistics companies are developing the infrastructure to solve that problem and attracting significant investment in the process.

Orbital Economics: Time, Cost and Risk

While governments have traditionally driven investment in satellite mobility and logistics, there is a growing commercial market centered on time and design flexibility. Depending on a satellite’s final orbit, the time penalty can be significant. Stefano Antonetti, vice president of business development at the Italian space logistics company D-Orbit, explained the economics of orbital drift.

“For satellites with limited or no propulsion, it’s the difference between a viable business case and a failed one,” Antonetti said.

Rideshares are not designed for precise orbital placement. A satellite left in a transfer orbit might spend months to a year using orbital drift to reach its final operating slot.

“The math simply works better with orbital transfer vehicles.” -Stefano Antonetti, D-Orbit

“For a satellite with a three-to-five-year design life, spending six months in transit means you’ve lost 10 to 15% of your revenue potential before you even start operations,” Antonetti said. “Instead of carrying their own propulsion systems—which add cost, complexity and points of failure—customers can delegate transportation to us and focus their resources on their actual payload and mission. The math simply works better with orbital transfer vehicles.”

That was not always the case. The dramatic reduction in launch costs and increasingly capable onboard robotics and autonomous systems have been important drivers in creating a market.

“While investment and enthusiasm are strong, customer demand—especially from government—has historically lagged due to concerns about cost and value,” said Bryan Hoke, corporate technical fellow for Dynamic Space Operations at The Aerospace Corporation. “This is starting to shift.”

Successful technology demonstrations are “beginning to reduce perceived risk, which will, in turn, increase government adoption and stimulate further commercial investment,” he said. Hoke cited NASA’s recent $30 million Phase III Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) contract with Katalyst Space Technologies for the robotic capture and orbit raising of the Swift Observatory. The U.S. Space Force is also partnering with Astroscale and Northrop Grumman for two separate refueling demonstrations in GEO, scheduled for 2026 and 2028 respectively.

A Market in Motion

Of all the emerging space industries, logistics has been the most active in recent years, according to Space Capital. Since 2019, 55 logistics companies have participated in 147 funding rounds, making it more active than commercial space stations, where 30 companies raised 72 rounds. 2025 is shaping up to be a top funding year for logistics, according to Space Capital’s Q3 report.

Government and defense spending is driving the most significant near-term. However, companies like D-Orbit are showing it’s possible to transition from early-stage institutional funding to commercially viable services. To date, D-Orbit has flown 19 missions with more than 200 payloads for institutional and research organizations as well as commercial entities, like Spire, Planet Labs and Astrocast.

Commercial growth is a critical marker of maturity, but government demand remains essential.

Commercial growth is a critical marker of maturity, but government demand remains essential. In the United States, there have been mixed signals. In 2023, the Space Force stood up the Servicing, Mobility and Logistics Office. It prioritized “dynamic space operations,” allocating $20 million in 2025 for research and development and technology demonstrations, such as on-orbit refueling and other mobility services. That support was reportedly pulled from the 2026 budget.

Maneuverability remains essential to the Space Force’s Tactically Responsive Space (TacRS) initiative. The VICTUS series of missions, which began with VICTUS NOX launching a satellite 27 hours after authorization, is scheduled to continue with the late-2025 launch of VICTUS HAZE. More recently, Space Systems Command awarded a $34.5 million contract to Impulse Space for VICTUS SURGO and VICTUS SALO, with two orbital maneuver vehicles capable of rapid response and asset repositioning expected to launch around mid-2026.

Unlike some markets that are wholly dependent on defense, the space logistics market shows positive signs of commercial sustainment.

“Space mobility and logistics are emerging markets with high potential,” Hoke said, “but long-term winners and profitability remain uncertain. Early entrants have opportunities to shape the market, yet competition will be intense.”

Players and Technology

Players in the space logistics market are focused on dual-use applications for orbital transfer vehicles and broader approaches.

Impulse Space has been flying missions since 2021 on its Mira orbital transfer vehicle that uses nitrous-based bipropellant thrusters for high-impulse orbital maneuvers. Impulse recently announced several commercial contracts, including a planned 2027 orbital insertion mission with Astranis. The company was also selected for the Space Force VICTUS SURGO rapid orbital insertion mission slated for 2026. Impulse has raised $525 million to date, including $300 million in Series C funding in June 2025.

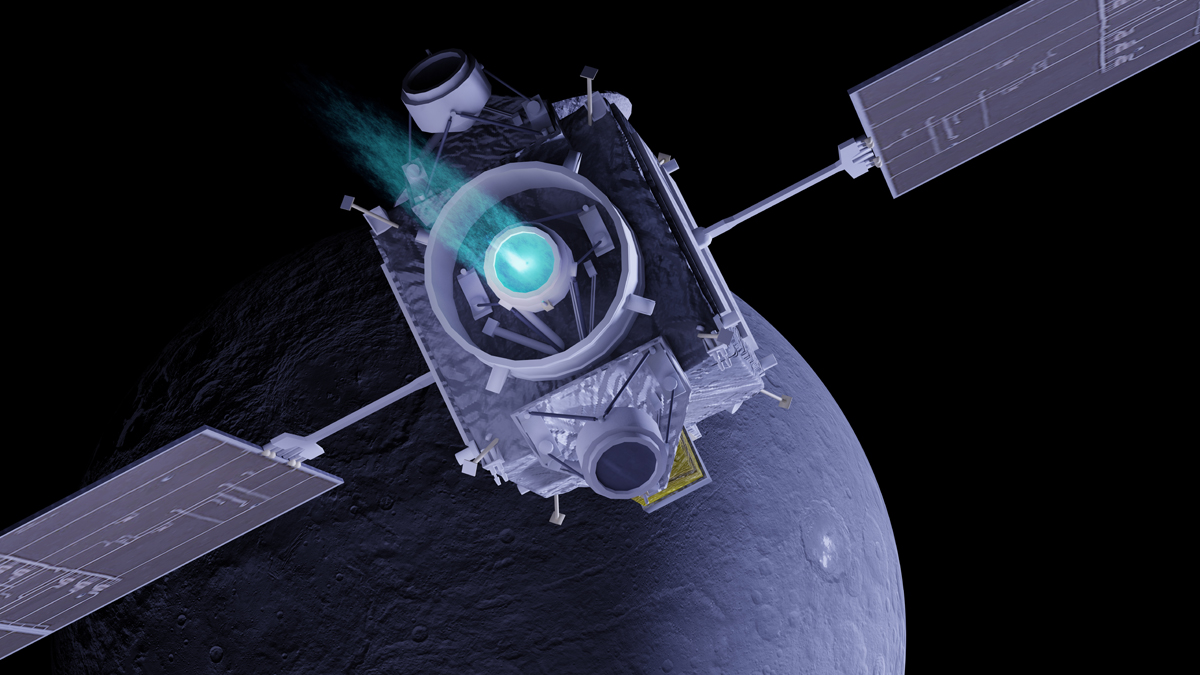

D-Orbit has been operating its high-impulse ION orbital transfer vehicle since September 2020, completing 19 missions and deploying more than 200 payloads. The ION platform, which has a configurable payload to carry and release spacecraft along distinct orbital planes. D-Orbit has raised approximately $256 million total and recently secured a $131 million (€119.6 million) ESA contract for the RISE mission to develop its GEA satellite servicing vehicle, set for 2028.

ExoTrail, the French space mobility company, has raised $74.6 million in total funding, largely for the Spacevan orbital vehicle designed for small satellites. The first Spacevan mission was in November 2023 and successfully deployed an 8U cubesat manufactured by Endurosat with an Airbus Defense and Space payload. Its customers include Eutelsat, Airbus, Thales Alenia Space and York Space Systems, and it has institutional contracts with NASA and the French Space Command. A GEO version of Spacevan launches on Ariane 6 in 2026, designed to deliver up to 150 kg from geostationary transfer orbit to GEO in under six months.

TransAstra is developing the Worker Bee orbital transfer vehicle, which uses water as propellant via solar thermal propulsion for last-mile satellite delivery. The company has raised approximately $12 million in private capital and $15 million from contracts and grants with NASA and the Space Force.

Stoke Space Technologies has raised $990 million, including $510 million in Series D funding in October 2025, to scale its two-stage fully reusable Nova launch vehicle. Stoke’s reusable upper stage for unlimited engine restarts for access to high-energy orbits like GEO and translunar injection, as well as rendezvous, capture and repositioning of assets. The company was awarded a Space Force National Security Space Launch contract in March 2025 for its medium lift, reusable two-stage rocket.

True Anomaly is primarily focused on the defense market, developing the Jackal autonomous vehicle for tactical space domain awareness and maneuvering across multiple orbital regimes, up to cislunar space. True Anomaly successfully launched and controlled Jackal during its Mission X-2 demonstration and was awarded the contract for VICTUS HAZE.

Other notable players include Orbital Operations, which raised $8.8 million in seed funding in Q3 2025 for an orbital vehicle focused on national security missions, and K2 Space, which announced a three-orbit demonstration mission in late October to test a spacecraft across three orbital regimes in a single mission.

The 2035 Vision

The path forward for space mobility and logistics will depend on various factors in both the near and long term. Some key markers for near-term success: clear government demand and sustained funding, as well as the creation of frameworks that enable broad industry participation, like standardized docking, refueling and modular interfaces, Hoke said.

“Near-term success requires alignment across government, technology and industry, with a shared understanding of when space logistics infrastructure provides more value than mass proliferation—particularly for national security architectures that must operate through conflict,” Hoke said.

Looking even further into the future, D-Orbit envisions orbital vehicles as a permanent presence. Like airport taxis, these vehicles would be available to collect satellites from launchers from lower altitudes and transport them to their final destinations.

“This creates a fundamentally different architecture where OTVs are part of a larger infrastructure,” Antonetti said. That infrastructure would include servicing vehicles, like D-Orbit’s GEA, as well as refueling and orbital manufacturing nodes.

Longer-term success means “[m]ission design has transformed completely,” Antonetti continued. “Instead of over-engineering satellites to last 15 years, operators build simpler, cheaper platforms knowing they can be serviced and upgraded.” This change could shift launch away from precise final orbits to delivering mass to collection points and shift expenditures from high-cost individual satellites to space logistics infrastructure.

Today, the successful missions of orbital vehicles are shaping a market that would have been unthinkable a decade ago.

These capabilities may seem far off, but so was the idea of an orbital transfer vehicle. “When we started sharing this vision just a few years ago, people thought we were crazy,” Antonetti said. Today, the successful missions of orbital vehicles are shaping a market that would have been unthinkable a decade ago. “By 2035, what seems revolutionary today will be routine operations.”

Explore More:

On-Orbit Transport: Opening a New Space Economy

Rockets, Re-use and Return-to-Earth: Novel Approaches to Orbital Access

Podcast: Executive Insights with CEO and Co-Founder of True Anomaly

Podcast: On-Orbit Refueling, Hybrid Architecture and Dynamic Space Operations